Vistas de página en total

jueves, 28 de enero de 2016

martes, 26 de enero de 2016

lunes, 25 de enero de 2016

Feelings you may experience with Cancer

Fear It’s frightening to hear you have cancer. Most people cope

better when they know what to expect.

Anger

You may feel angry with health care professionals, your God,

or even yourself if you think you may have contributed to the

cancer or a delay in diagnosis.

Disbelief: You may have trouble accepting that you have cancer,

especially if you don’t feel sick. It may take time to accept

the diagnosis.

Sadness

It is natural for a person with cancer to feel sad. If you

have continual feelings of sadness, and feel sleepy

and unmotivated – talk to your doctor – you may be

clinically depressed.

Guilt It is common to look for a cause of cancer. While some

people blame themselves, no-one deserves to get cancer.

loneliness

It’s natural to feel that nobody understands what you’re

going through.

You might feel lonely and isolated if your

family and friends have trouble dealing with cancer, or if

you are too sick to work or socialise with others and enjoy

your usual activities.

Loss of

control

Being told you have cancer can be overwhelming and make

you feel as though you are losing control of your life.

Distress

Many people, including carers and family members,

experience high levels of emotional suffering as a direct

result of a cancer diagnosis.

Emotions and Cancer

A guide for people with cancer, their families and friends

First published July 2002. This edition April 2013.

© The Cancer Council NSW 2013

ISBN 978 1 921619 76 2

miércoles, 20 de enero de 2016

10 Ways to Catch a Liar

Experts have 10 tips that can let you know if someone isn't telling you the whole truth.

By Heather Hatfield

WebMD Feature

WebMD Feature

Reviewed by Louise Chang, MD

J.J. Newberry was a trained federal agent, skilled in the art of deception detection. So when a witness to a shooting sat in front of him and tried to tell him that when she heard gunshots she didn't look, she just ran -- he knew she was lying.

How did Newberry reach this conclusion? The answer is by recognizing telltale signs that a person isn't being honest, like inconsistencies in a story, behavior that's different from a person's norm, or too much detail in an explanation.

While using these signs to catch a liar takes extensive training and practice, it's no longer only for authorities like Newberry. Now, the average person can become adept at identifying dishonesty, and it's not as hard as you might think. Experts tell WebMD the top 10 ways to let the truth be known.

Tip No. 1: Inconsistencies

"When you want to know if someone is lying, look for inconsistencies in what they are saying," says Newberry, who was a federal agent for 30 years and a police officer for five.

When the woman he was questioning said she ran and hid after hearing gunshots -- without looking -- Newberry saw the inconsistency immediately.

"There was something that just didn't fit," says Newberry. "She heard gunshots but she didn't look? I knew that was inconsistent with how a person would respond to a situation like that."

So when she wasn't paying attention, he banged on the table. She looked right at him.

"When a person hears a noise, it's a natural reaction to look toward it," Newberry tells WebMD. "I knew she heard those gunshots, looked in the direction from which they came, saw the shooter, and then ran."

Sure enough, he was right.

"Her story was just illogical," says Newberry. "And that's what you should look for when you're talking to someone who isn't being truthful. Are there inconsistencies that just don't fit?"

Tip No. 2: Ask the Unexpected

"About 4% of people are accomplished liars and they can do it well," says Newberry. "But because there are no Pinocchio responses to a lie, you have to catch them in it."

Sir Walter Scott put it best: "Oh what a tangled web we weave, when first we practice to deceive!" But how can you a catch a person in his own web of lies?

"Watch them carefully," says Newberry. "And then when they don't expect it, ask them one question that they are not prepared to answer to trip them up."

Tip No. 3: Gauge Against a Baseline

"One of the most important indicators of dishonesty is changes in behavior," says Maureen O'Sullivan, PhD, a professor of psychology at the University of San Francisco. "You want to pay attention to someone who is generally anxious, but now looks calm. Or, someone who is generally calm but now looks anxious."

The trick, explains O'Sullivan, is to gauge their behavior against a baseline. Is a person's behavior falling away from how they would normally act? If it is, that could mean that something is up.

Tip No. 4: Look for Insincere Emotions

"Most people can't fake smile," says O'Sullivan. "The timing will be wrong, it will be held too long, or it will be blended with other things. Maybe it will be a combination of an angry face with a smile; you can tell because their lips are smaller and less full than in a sincere smile."

These fake emotions are a good indicator that something has gone afoul.

Tip No. 5: Pay Attention to Gut Reactions

"People say, 'Oh, it was a gut reaction or women's intuition,' but what I think they are picking up on are the deviations of true emotions," O'Sullivan tells WebMD.

While an average person might not know what it is he's seeing when he thinks someone isn't being honest and attribute his suspicion to instinct, a scientist would be able to pinpoint it exactly -- which leads us to tip no. 6.

Tip No. 6: Watch for Microexpressions

When Joe Schmo has a gut feeling, Paul Ekman, a renowned expert in lie detection, sees microexpressions.

"A microexpression is a very brief expression, usually about a 25th of a second, that is always a concealed emotion," says Ekman, PhD, professor emeritus of psychology at the University of California Medical School in San Francisco.

So when a person is acting happy, but in actuality is really upset about something, for instance, his true emotion will be revealed in a subconscious flash of anger on his face. Whether the concealed emotion is fear, anger, happiness, or jealousy, that feeling will appear on the face in the blink of an eye. The trick is to see it.

"Almost everyone -- 99% of those we've tested in about 10,000 people -- won't see them," says Ekman. "But it can be taught."

In fact, in less than an hour, the average person can learn to see microexpressions.

Tip No. 7: Look for Contradictions

"The general rule is anything that a person does with their voice or their gesture that doesn't fit the words they are saying can indicate a lie," says Ekman. "For example, this is going to sound amazing, but it is true. Sometimes when people are lying and saying, 'Yes, she's the one that took the money,' they will without knowing it make a slight head shake 'no.' That's a gesture and it completely contradicts what they're saying in words."

These contradictions, explains Ekman, can be between the voice and the words, the gesture and the voice, the gesture and the words, or the face and the words.

"It's some aspect of demeanor that is contradicting another aspect," Ekman tells WebMD.

Tip No. 8: A Sense of Unease

"When someone isn't making eye contact and that's against how they normally act, it can mean they're not being honest," says Jenn Berman, PhD, a psychologist in private practice. "They look away, they'resweating, they look uneasy ... anything that isn't normal and indicatesanxiety."

Tip No. 9: Too Much Detail

"When you say to someone, 'Oh, where were you?' and they say, 'I went to the store and I needed to get eggs and milk and sugar and I almost hit a dog so I had to go slow,' and on and on, they're giving you too much detail," says Berman.

Too much detail could mean they've put a lot of thought into how they're going to get out of a situation and they've crafted a complicated lie as a solution.

Tip No. 10: Don't Ignore the Truth

"It's more important to recognize when someone is telling the truth than telling a lie because people can look like they're lying but be telling truth," says Newberry.

While it sounds confusing, finding the truth buried under a lie can sometimes help find the answer to an important question: Why is a person lying?

These 10 truth tips, experts agree, all help detect deception. What they don't do is tell you why a person is lying and what the lie means.

"Microexpressions don't tell you the reason," says Ekman. "They just tell you what the concealed emotion is and that there is an emotion being concealed."

When you think someone is lying, you have to either know the person well enough to understand why he or she might lie, or be a people expert.

"You can see a microexpression, but you have to have more social-emotional intelligence on people to use it accurately," says O'Sullivan. "You have to be a good judge of people to understand what it means."

Extra Tip: Be Trusting

"In general we have a choice about which stance we take in life," says Ekman. "If we take a suspicious stance life is not going to be too pleasant, but we won't get misled very often. If we take a trusting stance, life is going to be a lot more pleasant but sometimes we are going to be taken in. As a parent or a friend, you're much better off being trusting rather than looking for lies all the time."

Inside the Mind of a Psychopath – Empathic, But Not Always

Brain imaging shows psychopaths can empathize but do not empathize spontaneously

Posted Jul 24, 2013

To be sure, most psychopaths neither have Hannibal Lecter’s brilliant mind nor his rather peculiar culinary taste. They usually do not eat the liver of their victims. And yet, Lecter’s character does illustrate one of the conundrums of psychopathy: they can be socially cunning if they want to. They are able to seduce their victims into a dark alley, and, seconds later, turn into cold blooded rapists or murderers. Unlike most murderers, who act in the heat of a passion, and later feel guilty about what they have done, psychopaths feel no such remorse.

Prof. Keysers scans a participant

Source: (c) Valeria Gazzola

So far, the dominant understanding of psychopathy was that they basically lack emotions such as fear or distress. If you clap your hands behind someone’s back, she will startle, and you can measure how her palms get sweaty. If you do that with individuals with psychopathy, experiments have shown that their response is flattened. They barely startle and their hands stay dry. Now imagine, if you had never felt real fear or distress, how could you empathize with the fear or distress of others?

Empathy is key to our normal moral development. As kids, we are told not to hurt others, and we are told not to speak with our mouth full. Kids quickly come to feel very different about violating these two types of rules. Empathy is what makes the difference. Each time you hurt someone, that person’s distress becomes your pain, and you start to associate your vicarious pain with harming others. Violence then starts to feel intrinsically bad. Helping others, on the other hand, makes you feel their happiness, and will start to feel good.

If you were to lack empathy, this would never happen. Hurting others would leave you numb, and be as trivial as eating with your mouth full - just another convention. In that case, the only reason for doing neither would be fear of punishment – not guilt or compassion. If such an unempathic man would be alone in a dark alley with an attractive women and no one to punish him what would stand in the way of his lust?

To better understand whether a lack of empathy could explain why psychopathic offenders fail to feel bad about hurting others, we teamed up with a Dutch forensic clinic to investigate what happens in the brain. Over the last two decades, work from our lab and others has identified the neural signature of empathy. We all activate brain regions involved in our own actions, when we see the actions of others – even monkeys do so, as our work on mirror neurons has shown. We activate our somatosensory cortex, a region involved in sensing touch, when we see someone else touched on her skin. We activate our insula and cingulate cortex, regions involved in our own emotions, when we see the emotions of others. So if we witness a victim of violence wince in pain, our brain activates our own wincing and pain – we share her suffering. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging, we can quantify this empathy by simply measuring the activity in motor, somatosensory and emotional brain regions while witnessing the predicament of others.

To test if psychopathic individuals lack this empathic brain activation, the clinic transported 21

A participants about to be scanned

Source: Copyright Valeria Gazzola

convicted violent psychopathic offenders to our scanner. One by one, in bullet proof minivans. Because metal cannot be brought in the vicinity of magnetic imaging scanner, the guards were unarmed, but the patients had wooden sticks sawn into their trousers and plastic hand-cuffs to keep them from running away or hurting anyone.

Each patient was then shown movies of people hurting each other while brain activity was measured using fMRI. First, patients were simply told to watch the movies carefully. Later, Harma Meffert, the doctoral student who conducted the study (now at NIMH in Bethesda) went into the scanner room and slapped the patients on their hands to localize brain regions involved in feeling touch and pain. We could then zoom into these brain regions to see if the patients activated their own pain while viewing that of others. We did the same with 26 men of similar age and IQ. The results of the study, which are published today in the journal Brain(link is external), indicate that the vicarious activation of motor, somatosensory and emotional brain regions was much lower in the patients with psychopathy than in the normal subjects. The theory seemed right: their empathy was reduced, and this could explain why they committed such terrible crimes without feeling guilt.

Localizing pain regions

Source: Copyright Valeria Gazzola

But then, how can they be so charming at times? I remember chatting with one of the patients, Patient 13, a particularly severe psychopath (he had scored the full 40 points on the psychopathy checklist). Surrounded by the guards, he seemed a most pleasant person. He was smiling, engaging, and seemed to feel exactly what we wanted from him. Many of our ‘normal’ participants seemed rough and unfriendly in comparison. Valeria Gazzola, with whom I lead the lab, suggested that we let the patients watch the movies again, but asking them to try and empathize with the victims in the movies. What we found was that this simple instruction sufficed to boost the empathic activation in their brain to a level that was hard to distinguish from that of the healthy controls. Suddenly, the psychopaths seemed as empathic as the next guy. Their empathy was switched on.

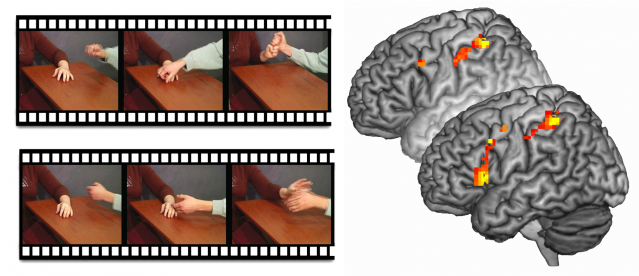

Reduced spontaneous (back) but normal deliberate (front) brain activity in psychopathic criminals while viewing movies

So psychopathic individuals do not simply lack empathy. Instead, it seems as though for most of us, empathy is the default mode. If we see a victim, we share her pain. For the psychopathic criminals of our study, empathy seemed to be a voluntary activity. If they want to, they can empathize, and that explains how they can be so charming, and maybe so manipulative. Once they have seduced you into doing what serves their purpose, the effortful empathy would though probably disappear again. Free of the constraints of empathy, they is then little to stop them from using violence.

How can psychopathic individuals switch their empathy on and off? All of us have such a switch. We are more empathic towards the pain of our friends, than towards the misery of the people on the other side of the globe. Acupunctures learn to supress their empathy to the sight of a needle entering skin. Reducing empathy, sometimes, has clear evolutionary benefits: if you need to defend your family from an attack, you cannot afford to empathize with your aggressor. Our default mode, however, seems to have our empathy on. Individuals with psychopathy seem to have a slightly different switch: their default mode seems to be off. But

Much still needs to be understood about why and how individuals with psychopathy seem to have the potential to empathize sometimes but have this capacity switched off by default. For therapists, our finding suggests that the best approach may not be to teach them empathy - they already seem capable of empathy. Instead, therapies may need to learn to be empathic always. How to do so is unclear, but it might be best to start such training early, before violence has become a way of life. A recent study from the group of Essi Viding at the UCL(link is external) in London has shown that a callous unemotional subgroup of kids with conduct disorder already seem to lack spontaneous empathy: they also activate their empathic brain less when simply watching others in pain. These kids are known to have a heightened risk of becoming psychopathic adults. Intervening early, in these children, to make empathy automatic, might be a promising approach.

For more information about the neural basis of empathy and psychopathy, have a look at the book The Empathic Brain(link is external).

Suscribirse a:

Entradas (Atom)

16 Questions That Might Tell You Whether You're A Sociopath

1. Are you superficially charming and intelligent?

© Provided by Business Insider2. Do you have delusions or other signs of irrational thinking?

© Provided by Business Insider3. Are you overly nervous, or do you have other neuroses?

© Provided by Business Insider4. Are you reliable?

© Provided by Business Insider5. Do you tell lies or say insincere things?

© Provided by Business Insider6. Do you feel remorse or shame?

© Provided by Business Insider7. Is your behavior anti-social for no good reason?

8. Do you have poor judgment, and fail to learn from experience?

© Provided by Business Insider9. Are you pathologically egocentric, and incapable of love?

© Oliver Eltinger/Corbis Egocentric man10. Do you generally lack the ability to react emotionally?

© Provided by Business Insider11. Do you lack insight?

© Provided by Business Insider12. Are you responsive to others socially?

© Provided by Business Insider13. Are you a crazy party fiend?

© Provided by Business Insider14. Do you make false suicide threats?

© Provided by Business Insider15. Is your sex life impersonal, trivial or poorly integrated?

© Provided by Business Insider16. Have you failed to follow a life plan?

© Provided by Business InsiderThere's no surefire way of self-diagnosing yourself as a sociopath, as sociopaths also tend to lie in tests like these.

© Provided by Business Insider